Introduction to Bash

Don’t forget this week’s reading.

In this note, we discuss the Unix shell and its commands. The ‘shell’ is a command-line interpreter and invokes kernel-level commands. It also can be used as a programming language to design your own commands. We’ll come to shell programming in a future note.

We do not recommend that you buy a book about Unix or the shell; there are some very good references and free-access online books – see the resources page – and we have selected some interesting and useful readings.

If you need help on the meaning or syntax of any Unix shell command you can use the manual (man) pages on a Unix system (see below) or the web unix commands. Just keep in mind that some commands’ syntax varies a bit across Unix flavors, so when in doubt, check the man page on the system you’re using.

Unix Philosophy

In their book Program Design in the Unix Environment (1984), Rob Pike and Brian Kernighan put it this way:

``Much of the power of the Unix operating system comes from a style of program design that makes programs easy to use and, more important, easy to combine with other programs. This style has been called the use of software tools, and depends more on how the programs fit into the programming environment and how they can be used with other programs than on how they are designed internally. This style was based on the use of tools: using programs separately or in combination to get a job done, rather than doing it by hand, by monolithic self-sufficient subsystems, or by special-purpose, one-time programs.’’

Historical note - Unix

Unix was developed at Bell Labs in the 1970s by a group led by Doug McIlroy.

``This is the Unix philosophy: Write programs that do one thing and do it well. Write programs to work together. Write programs to handle text streams, because that is a universal interface.’’ — Doug McIlroy

Goals

We plan to cover the following topics in this note.

- The shell

- The file system

The shell

Commands, switches, arguments

The shell is the Unix command-line interpreter. It provides an

interface between the user and the kernel and executes programs called

‘commands’. For example, if a user enters ls then the shell

executes the ls command, which actually executes a program stored in

the file /bin/ls. The shell can also execute other programs

including scripts (text files interpreted by a program like python or

bash) and compiled programs (e.g., written in C). Even your own

programs – once marked ‘executable’ – become commands you can run

from the shell!

You will get by in the course by becoming familiar with a subset of the Unix commands; don’t let yourself be overwhelmed by the presence of hundreds of commands. You will probably be regularly using 2-3 dozen of them by the end of the term.

Unix has often been criticized for being very terse (it’s rumored that its designers were bad typists). Many commands have short, cryptic names and vowels are a rarity:

awk, cat, cp, cd, chmod, echo, find, grep, ls, mv, rm, tr, sed, comm

We will learn to use all of these commands and more.

Unix command output is also very terse - the default action on success is silence. Only errors are reported, and error messages are often terse. Unix commands are often termed ‘tools’ or ‘utilities’, because they are meant to be simple tools that you can combine in novel ways.

Instructions entered in response to the shell prompt are interpreted first by the shell - expanding any variable references, filename wildcards, or special syntax. Thus, the shell can rewrite the command line; then, it expects the command line to have the following syntax:

command [arg1]...

The brackets [ ] indicate that the arguments are optional, and the

notation above means that there are zero or more arguments. Arguments

are separated by white space. Many commands can be executed with or

without arguments. Others require arguments, or a certain number of

arguments, (e.g., cp sort.c anothersort.c) to work correctly. If

none are supplied, they will provide some error message in return.

Another part of the Unix philosophy is to avoid an explosion in the

number of commands by having most commands support various options

(sometimes called flags or switches), which modify the actions of

the commands.

For example, let’s use the ls command and the -l option switch to

list in long format the file filename.c.

ls -l filename.c

Switches are often single characters preceded by a hyphen (e.g.,

-l). Most commands accept switches in any order, though they

generally must appear before all the real arguments (usually

filenames). In the case of the ls example below, the command

arguments represent file or directory names. The options modify the

operation of the command and are usually operated on by the program

invoked by the shell rather than the shell itself.

Unix programs always receive a list of arguments, containing at least

one argument, which is always the command name itself. So, for ls

that first argument would be “ls”. The first argument is referred

to as argument 0, “the zero-th argument”. In our ls example,

argument 1 is -l and argument 2 is filename.c. Some commands also

accept their switches grouped together. For example, the following

switches to ls are identical:

ls -tla foople*

...

ls -t -l -a foople*

The shell parses the words or tokens (command name and arguments) you type on the command line, and asks the kernel to execute the program corresponding to that command; the interpretation of the arguments (as switches, filenames, or something else) is determined by that program.

Typically, the shell processes the complete line after a carriage

return is entered and then goes off to find the program that the

command line specified. If the command is a pathname, whether

relative (e.g., ./mycommand) or absolute (e.g., /bin/ls or

~engs50/mycommand), the shell simply executes the program in that

file. If the command is not a pathname, the shell searches through a

list of directories in your “path”, which is defined by the shell

variable called PATH.

Shell’s ‘Path’

Take a look at your PATH by asking the shell to substitute its value

($PATH) and pass it as an argument to the echo command:

[engs50@mc ~]$ echo $PATH

/usr/lib64/qt-3.3/bin:/usr/lib64/ccache:/usr/local/bin:/usr/bin:/usr/local/sbin:/usr/sbin:/net/class/engs50/bin:/bin:/usr/bin:/sbin:/usr/sbin:/usr/java/j2sdk/bin:/usr/local/bin:/usr/local/bin/X11:.

[engs50@mc ~]$

Note that in general the output from the commands shown in this note demonstrate notional output. You will not see exactly the same information portrayed if you execute the same commands. Shell prompts show you the current user, machine, and location e.g.

[engs50@mc ~]$

is a shell prompt ($) for user “engs50” on machine “mc” with the shell currently in the users home directory (~).

So where does the ls command executed above reside in the Unix directory hierarchy?

Let’s use another command to find out.

[engs50@mc ~]$ which ls

ls is aliased to `ls -F'

ls is /usr/bin/ls

ls is /bin/ls

ls is /usr/bin/ls

[engs50@mc ~]$

The first line of response says that ls is “aliased”. This is a

shell feature; the shell allows us to define “aliases”, which act just

like commands but are actually just a textual substitution of a

command name (the alias) to some other string (in this case, ls -F).

Thus, any time I type ls blah blah, it treats it as if I had typed

ls -F blah blah. The -F option tells ls to add a trailing

symbol to some names in its output; it adds a / to the names of

directories, a @ to the names of symbolic links (um, that’s another

conversation), and some other even specialized cases.

Of course, the shell then still needs to resolve ls. It then

searches the PATH to find an executable file with that name; in this

case, it appears that ls exists in both /usr/bin and in /bin.

The shell will execute the first one, because it is found first in the

PATH. Below you can see the effect of running ls (the alias) and

/bin/ls (the raw command, without the -F).

[engs50@mc ~]$ ls

Archive/ private/ proc-log public_html/ resources/ web@

[engs50@mc ~]$ /bin/ls

Archive private proc-log public_html resources web

[engs50@mc ~]$

Viewing files

You can see the contents of any file with the cat command, so named because it concatenates all the files listed as arguments, printing one after the other.

For very long files, though, the output will quickly scroll off your terminal.

Less Is More: The less and more commands are handy for quickly looking at files.

The syntax is less filename and more filename.

Take a look at the man pages to get the details of each.

Similarly, head and tail display a number of lines (selectable via switches, of course) at the beginning and end of a file, respectively.

See what these do: cat /etc/passwd, head /etc/passwd, tail /etc/passwd, more /etc/passwd, and less /etc/passwd.

The file /etc/passwd lists all the accounts on the system, and information about each account.

Editing files

Long before there were windows and graphical displays, or even

screens, there were text editors. Two are in common use on Unix

system today: emacs and vi. Actually, there is an

expanded/improved version of vi called vim, which is quite

popular.

I strongly recommend emacs if you are planning to take Engs62 – our embedded systems course, since the Xilinx vivado tool chain provides an Emacs mode for editing. Also, you will find that many emacs commands are available in bash for working at the command line.

You should try both and become comfortable with at least one. Yes, it’s tempting to use an external graphical editor (like Sublime), but it is frequently the case when working with embedded systems and/or servers that there simply is not a graphical user interface; in these cases you must use a text-only editor so you should get used to it now.

See /engs50/Resources/#editors for some resources that can help you

learn emacs or vim. I’ve provided a 15 min – “Learn Emacs Fast”

video to help.

Unix file system

The Unix file system is a hierarchical file system. The file system consists of a very small number of different file types. The two most common types are files and directories.

A directory (akin to a folder on a MacOS or Windows computer) contains

the names and locations of all files and directories below it. A

directory always contains two special files . (dot) and .. (dot

dot); . represents the directory itself, and .. represents the

directory’s parent. In the following, I make a new directory, change

my current working directory to be that new directory, create a new

file in that directory, and use ls to explore the contents of the

new directory and its parent.

[engs50@mc ~]$ mkdir test

[engs50@mc ~]$ cd test

[engs50@mc ~/test]$ echo hello > somefile

[engs50@mc ~/test]$ ls -a

./ ../ somefile

[engs50@mc ~/test]$ ls

somefile

[engs50@mc ~/test]$ ls .

somefile

[engs50@mc ~/test]$ ls ..

Archive/ private/ proc-log public_html/ resources/ test/ web@

[engs50@mc ~/test]$

Directory names are separated by a forward slash /, forming

pathnames. A pathname is a filename that includes some or all of

the directories leading to the file; an absolute pathname is

relative to the root (/) directory and begins with a /, in the

first example below, whereas a relative pathname is relative to the

current working directory, as in the second example below. Notice

that a relative pathname can also use . or .., as in the third

example below.

[engs50@mc ~]$ ls /net/class/engs50/public_html/Labs/*

/net/class/engs50/public_html/Labs/index.html

/net/class/engs50/public_html/Labs/Lab0-Preliminaries.html

/net/class/engs50/public_html/Labs/usernames.txt

[engs50@mc ~]$ ls public_html/Resources/*

public_html/Resources/DougMcIlroy.pdf

public_html/Resources/Homebrew0.png

public_html/Resources/Homebrew1.png

public_html/Resources/Homebrew.html

public_html/Resources/index.html

public_html/Resources/RC13972-C-Programming.docx

public_html/Resources/RC13972-C-Programming.pdf

public_html/Resources/StartingSublime.pdf

public_html/Resources/toomey-unix.pdf

[engs50@mc ~]$ ls ../cs10/public_html/

azul.css help.html lab/ oldindex.html software.html

exams/ indexBAK.html lectures/ sa/ syllabus.html

exams.html index.html old/ schedule.html

[engs50@mc ~]$

As implied by the shell prompt, the current working directory is

~engs50, which is shorthand for “the home directory of user

engs50”, which happens to be the directory at path

/net/class/engs50.

Moving around the file system

The “change directory” command (cd) allows us to move around the

Unix directory hierarchy, that is, to change our “current working

directory” from which all relative filenames and pathnames will be

resolved. Let’s combine pwd, ls, and cd to move around the

local directories that are rooted at /net/class/engs50. Remember that

~ refers to the home directory and .. refers to the parent

directory.

[engs50@mc ~]$ mkdir test

[engs50@mc ~]$ cd test

[engs50@mc ~/test]$ ls

[engs50@mc ~/test]$ cd ..

[engs50@mc ~]$ cd public_html/

[engs50@mc ~/public_html]$ ls

css/ Labs/ Logistics/ Reading/ Schedule.pdf

index.html Notes/ Project/ Resources/ Schedule.xlsx

[engs50@mc ~/public_html]$ cd Resources/

[engs50@mc ~/public_html/Resources]$ ls

DougMcIlroy.pdf Homebrew.html RC13972-C-Programming.pdf

Homebrew0.png index.html StartingSublime.pdf

Homebrew1.png RC13972-C-Programming.docx toomey-unix.pdf

[engs50@mc ~/public_html/Resources]$ cd ../..

[engs50@mc ~]$ ls

Archive/ private/ proc-log public_html/ resources/ test/ web@

[engs50@mc ~]$

The shell prompt is helpfully tracking the current working directory as we move.

Listing and globbing files

Here are a popular set of switches you can use with ls:

-l list in long format (as we have been doing)

-a list all entries (including `dot` files, which are normally hidden)

-t sort by modification time (latest first)

-r list in reverse order (alphabetical or time)

-R list the directory and its subdirectories recursively

The shell also interprets certain special characters like *, ?,

and []; * matches zero or more characters, ? matches one

character, and [] matches one character from the set (or range) of

characters listed within the brackets:

[engs50@mc ~]$ cd public_html/Resources/

[engs50@mc ~/public_html/Resources]$ ls

DougMcIlroy.pdf Homebrew.html RC13972-C-Programming.pdf

Homebrew0.png index.html StartingSublime.pdf

Homebrew1.png RC13972-C-Programming.docx toomey-unix.pdf

[engs50@mc ~/public_html/Resources]$ ls *.pdf

DougMcIlroy.pdf StartingSublime.pdf

RC13972-C-Programming.pdf toomey-unix.pdf

[engs50@mc ~/public_html/Resources]$ ls H*

Homebrew0.png Homebrew1.png Homebrew.html

[engs50@mc ~/public_html/Resources]$ ls *-*

RC13972-C-Programming.docx RC13972-C-Programming.pdf toomey-unix.pdf

[engs50@mc ~/public_html/Resources]$ ls Homebrew*.*

Homebrew0.png Homebrew1.png Homebrew.html

[engs50@mc ~/public_html/Resources]$ ls Homebrew?.*

Homebrew0.png Homebrew1.png

[engs50@mc ~/public_html/Resources]$ ls Homebrew[0-9].png

Homebrew0.png Homebrew1.png

[engs50@mc ~/public_html/Resources]$

Hidden files

The ls program normally does not list any files whose filename begins with . There is nothing special about these files, except . and .., as far as Unix is concerned.

It’s simply a convention - files whose names begin with . are to be considered ‘hidden’, and thus not listed by ls or matched with by the shell’s * globbing character.

Home directories, in particular, include many ‘hidden’ (but important!) files.

The -a switch tells ls to list “all” files, including those that begin with a dot (aka, the hidden files).

[engs50@mc ~]$ ls

Archive/ private/ public_html/ resources/ web@

[engs50@mc ~]$ ls -a

./ Archive/ .bash_logout .bashrc .environset private/ public_html/ .ssh/ .viminfo web@

../ .bash_history .bash_profile .emacs.d/ .forward .procmailrc resources/ .vim/ .vimrc

to see just the dot files, let’s get clever with the shell’s glob characters:

[engs50@mc ~]$ ls -ad .??*

.bash_history .bash_profile .emacs.d/ .forward .ssh/ .viminfo

.bash_logout .bashrc .environset .procmailrc .vim/ .vimrc

[engs50@mc ~]$

All of these “dot files” (or “dot directories”) are important to one program or another:

.bash_history- used by bash to record a history of the commands you’ve typed.bash_logout- executed by bash when you log out.bash_profile- executed by bash when you log in.bashrc- executed by bash whenever you start a new shell.emacs.d/- a directory used by emacs text editor.environset- a Dartmouth-specific thing; read by .bashrc.forward- tells Mail where to forwad your email.procmailrc- for handling email withprocmail.ssh/- directory used by inbound ssh connections.vim/- a directory used by vim text editor.viminfo- used by vim text editor.vimrc- used by vim text editor

Bash shell startup files

The bash shell looks for several files in your home directory:

.bash_profile- executed by bash when you log in.bashrc- executed by bash whenever you start a new shell.bash_logout- executed by bash when you log out.bash_history- used by bash to record a history of the commands you’ve typed

The .bashrc file is especially important, because bash reads it

every time you start a new bash shell, that is, when you log in,

when you start a new interactive shell, or when you run a new bash

script. (In contrast, .bash_profile is only read when you login.)

In each case,bash reads the files and executes the commands therein.

Thus, you can configure your bash experience by having it declare

some variables, define some aliases, and set up some personal

favorites.

Locating files

Many times you want to find a file but do not know where it is in the

directory tree (Unix directory structure is a tree - rooted at the /

directory) . The find command can walk a file hierarchy:

[engs50@mc ~]$ find . -name DougMcIlroy.pdf -print

./public_html/Resources/DougMcIlroy.pdf

[engs50@mc ~]$ find public_html -iname reading -print

public_html/Reading

[engs50@mc ~]$ find public_html -type d -print

public_html

public_html/Logistics

public_html/Resources

public_html/Labs

public_html/Project

public_html/Notes

public_html/css

public_html/Reading

[engs50@mc ~]$ find public_html -name \*.html -print

public_html/Logistics/index.html

public_html/Resources/index.html

public_html/Resources/Homebrew.html

public_html/Labs/index.html

public_html/Labs/Lab0-Preliminaries.html

public_html/Project/index.html

public_html/Notes/01-gettingstarted.html

public_html/Notes/index.html

public_html/index.html

public_html/Reading/index.html

[engs50@mc ~]$ find public_html -name \*.png -mtime -1 -print

public_html/Resources/Homebrew1.png

public_html/Resources/Homebrew0.png

[engs50@mc ~]$

The first example searches directory . to find a file by a specific

name and prints its pathname. The second example used -iname (case

insensitive search) instead of -name (which is case sensitive) to

search public_html for the “reading” directory. The third example

searches public_html for any directories (-type d) and prints

their pathnames. The fourth example uses a wildcard * to print

pathnames of files whose name matches a pattern; the backslash \ is

there to prevent the shell from interpreting the *, allowing it to

be part of the argument to find, which interprets that character

itself. The fifth example combines two factors, to print pathnames of

files whose name matches *.png and whose modication time mtime is

less than one day -1 in the past.

Our top commands

We’ve explored almost four dozen shell commands, below (those with *asterisk will be introduced later). You’ll often need only about half of them.

alias

cat, cd, chmod, comm, cp, cut

date

echo, emacs, expr, exit

file, find

gcc, gdb*, git*, grep

head

less, logout, lpr, ls

make*, man, mkdir, more, mv

open (MacOS)

pbpaste, pbcopy (MacOS)

pwd

rm, rmdir

scp, sed, sort, ssh

tail, tar, touch, tr

uniq

whereis, which

vi, vim

Historical note

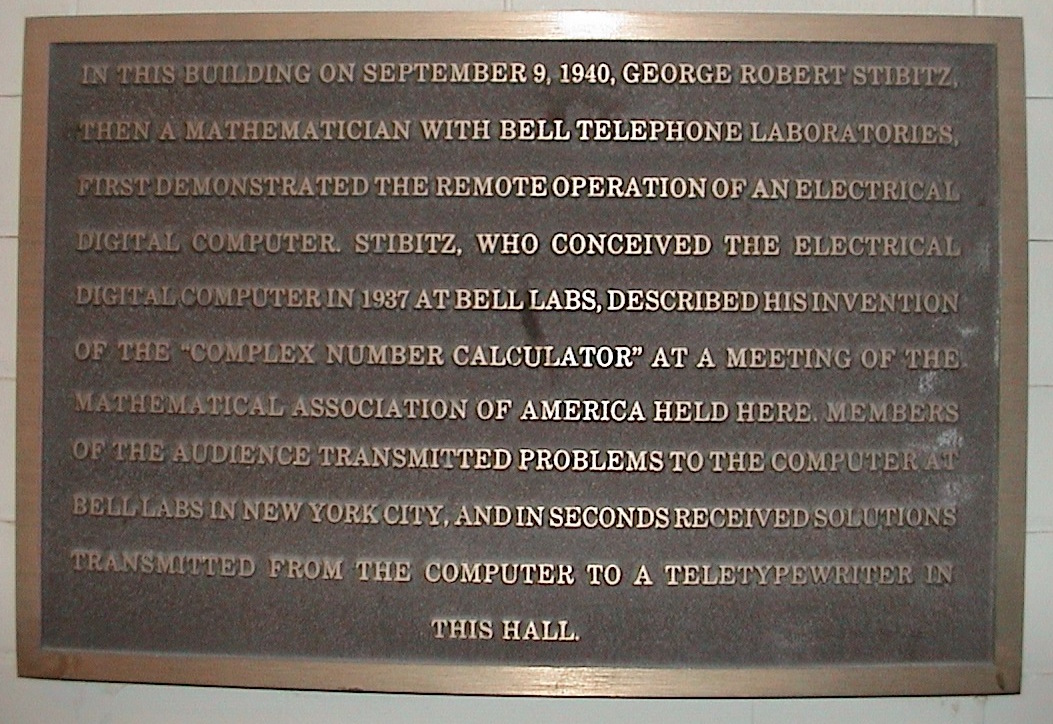

Recall we mentioned “teletypes” in the first lecture. It was at Dartmouth that a teletype was actually used to interact with a remote computer - the first ever long-distance terminal, decades before the Internet.

Navigating within man pages

You may have found the man system to be a little challenging to navigate.

There is a message that is displayed at the very bottom of the screen when you first enter the command that you might have missed (most people do):

Manual page xxx(n) line 1 (press h for help or q to quit)

If you enter ‘h’ to see the help you will find many more commands than you’re likely to ever use when reading man pages.

This is because the man-page reader is actually the less command of Unix.

I tend to use only a few:

for space (the spacebar) advances to the next screenful,bgoes back to the previous screenful,eor down-arrow advances one more line,yor up-arrow goes back one line,/allows one to type a search phrase and hit return,qquitsman, and returns to the shell prompt.

There are shells, shells, and more shells

There are a number of shells available to a Unix user – so which one do you select? The most common shells are:

sh: the original shell, known as the Bourne Shell,csh,tcsh: well-known and widely used derivatives of the Bourne shell,ksh: the Korn shell, andbash: the Bourne Again SHell, developed by GNU, is the most popular shell used for Linux.

bash is the default shell for new Unix accounts in our department.

The basic shell operation is as follows. The shell parses the command

line; the first word on the line is the command name. If the command

is an alias, it substitutes the alias text and again identifies the

command. If the command is one built-in to the shell (there are a

few, like cd, echo, pwd, and which) it performs that command’s

action. Otherwise, the shell looks for the executable file that

matches that program name by searching directories listed in the

PATH variable. The shell then starts that program as a new process

and passes any options and arguments to the program. A process is a

running program. You can see a list of your processes with the

command ps.

File type

Unix itself imposes almost no constraints or interpretation on the contents of files - the only common case is that of a compiled, executable program: it has to be in a very specific binary format for the operating system (Unix) to execute it. All other files are used by some program or another, and it’s up to those programs to interpret the contents as they see fit. The great power of Unix, and the common shell commands, is that any file can be read by any program; the most common format are plain-text (ASCII) files that are formatted as a series of “lines” delimited by “newline” characters (\n, known by its ASCII code 012).

If you are unsure about the contents of a file (text, binary,

compressed, Unix executabe, some format specific a certain

application, etc.). The file command is useful; it makes an attempt

to judge the format of the file.

[engs50@mc ~]$ file downloaded

downloaded: POSIX tar archive

[engs50@mc ~]$ file fig1

fig1: GIF image data, version 87a, 440 x 306

[engs50@mc ~]$ file trash.tar.gz

trash.tar.gz: gzip compressed data, from Unix

[engs50@mc ~]$ file public_html/Schedule.*

public_html/Schedule.pdf: PDF document, version 1.3

public_html/Schedule.xlsx: Microsoft Excel 2007+

[engs50@mc ~]$ file /bin/ls

/bin/ls: ELF 64-bit LSB shared object, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, interpreter /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2, for GNU/Linux 2.6.32, BuildID[sha1]=0ac5c509289d650534ce80cdbf5b72744b5c5f3d, stripped

[engs50@mc ~]$