TSE Crawler design and implementation

Goals

- To understand the specifications for the Tiny Search Engine (TSE)

- To develop an implementation plan for the TSE Crawler

- To demonstrate the execution of one Crawler solution

My first Terminal script shows a short run of crawler over the cs50 home directory.

My second Terminal script shows some short runs of crawler over the small ‘letters’ playground, then a run over the ‘wikipedia’ playground; I eventually killed the maxDepth=2 crawl because it takes a long time to finish.

Specifications

A good software implementation requires a good software design, and a good software design must be based on a clear set of requirements. We think about these specifications as a sort of “contract” between the programmer (who writes the code) and the customer (the ultimate user of the software). Thus, we need three specs:

- Requirements spec: specifies what the software must do

- Design spec: specifies the structure of the software in a language-independent, machine-dependent way

- Implementation spec: specifies the language-dependent, machine-dependent details of the implementation.

We’ll take a closer look at the design process in the next lecture. For today, let’s apply this approach to the TSE.

Tiny Search Engine (TSE)

Our Tiny Search Engine (TSE) design is inspired by the material in the paper Searching the Web, by Arvind Arasu, Junghoo Cho, Hector Garcia-Molina, Andreas Paepcke, and Sriram Raghavan (Stanford University); ACM Transactions on Internet Technology (TOIT), Volume 1, Issue 1 (August 2001).

TSE Requirements Spec

The Tiny Search Engine (TSE) shall consist of three subsystems:

- crawler, which crawls the web from a given seed to a given maxDepth and caches the content of the pages it finds, one page per file, in a given directory.

- indexer, which reads files from the given directory, builds an index that maps from words to pages (URLs), and writes that index to a given file.

- querier, which reads the index from a given file, and a query expressed as a set of words optionally combined by (AND, OR), and outputs a ranked list of pages (URLs) in which the given combination of words appear.

Each subsystem is a standalone program executed from the command line, but they inter-connect through files in the file system.

In a spec document, we write shall do to mean must do.

We’ll look deeper at the requirements for the each subsystem, later. First, let’s go to the next level on the overall TSE: the Design Spec.

TSE Design Spec

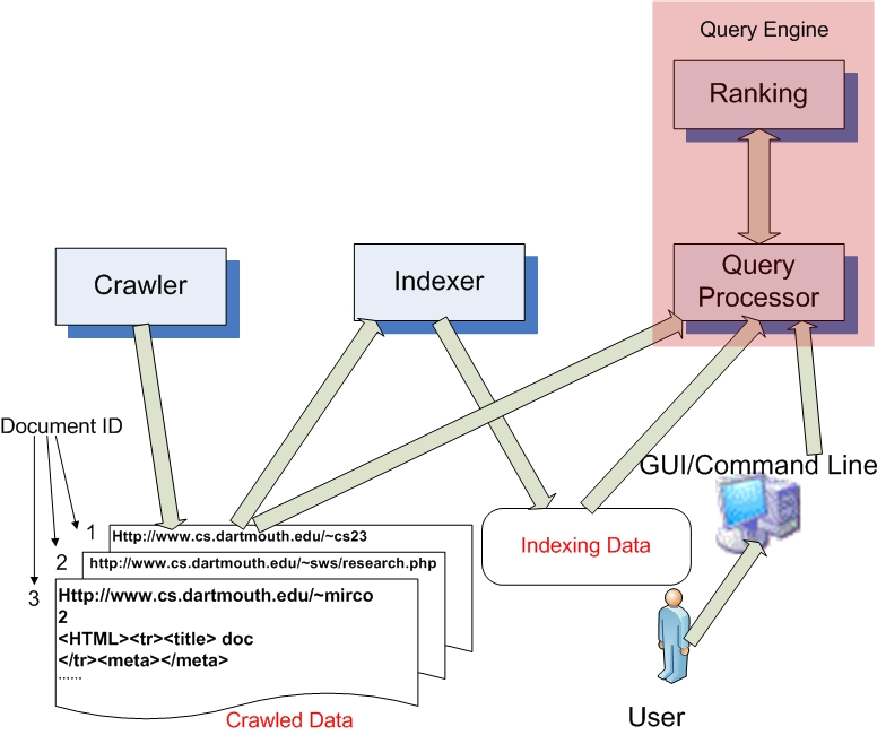

The overall architecture presented below shows the modular decomposition of the system:

The above diagram is consistent with the Requirements Spec: we can clearly see three sub-systems, their interconnection through files, and the user interface for submitting queries to the querier. The querier subsystem has an internal ranking module, which we anticipate might be separate from the query processor module; we’ll look more closely when we come to the querier design.

Next, we describe each sub-system and its high-level design.

The crawler crawls a website and retrieves webpages starting with a specified URL.

It parses the initial webpage, extracts any embedded href URLs and retrieves those pages, and crawls the pages found at those URLs, but limiting itself to maxDepth hops from the seed URL.

When the crawler process is complete, the indexing of the collected documents can begin.

The indexer extracts all the keywords for each stored webpage and creates a lookup table that maps each word found to all the documents (webpages) where the word was found.

The query engine responds to requests (queries) from users. The query processor module loads the index and searches for pages that include the search keywords. Because there may be many hits, we need a ranking module to rank the results (e.g., high to low number of instances of a keyword on a page).

TSE Crawler Specs

We’ll look deeper at the requirements for the indexer and querier later. Right now, let’s focus on the crawler:

- Requirements Spec.

- Design Spec.

- Implementation spec:

The Design Spec describes abstractions - abstract data structures, and pseudocode.

The same design could be implemented in C or Java or another language.

The Implementation Spec gets more specific.

It is language, operating system, and hardware dependent.

The implementation spec includes many or all of these topics:

- Detailed pseudo code for each of the objects/components/functions,

- Definition of detailed APIs, interfaces, function prototypes and their parameters,

- Data structures (e.g.,

structnames and members), - Security and privacy properties,

- Error handling and recovery,

- Resource management,

- Persistant storage (files, database, etc).

The Lab3 assignment is written like an implementation spec, right down to the specific function prototypes.

You need to write the Implementation spec for the Crawler in Lab 4.

Demonstration

Crawler execution and output

Below is a snippet of when the program starts to crawl the CS50 website to a depth of 1. The crawler prints status information as it goes along.

Note, you might consider covering this debugging print-out code in an

#ifdefblock that can be triggered by a compile-time switch. See the Lecture extra about this trick.

$ ./crawler http://old-www.cs.dartmouth.edu/~cs50/index.html data 1

0 Fetched: http://old-www.cs.dartmouth.edu/~cs50/index.html

0 Saved: http://old-www.cs.dartmouth.edu/~cs50/index.html

0 Scanning: http://old-www.cs.dartmouth.edu/~cs50/index.html

0 Found: http://old-www.cs.dartmouth.edu/~cs50/

0 Added: http://old-www.cs.dartmouth.edu/~cs50/

0 Found: https://canvas.dartmouth.edu/courses/14815

0 IgnExtrn: https://canvas.dartmouth.edu/courses/14815

0 Found: https://piazza.com/dartmouth/spring2017/cosc050sp17/home

0 IgnExtrn: https://piazza.com/dartmouth/spring2017/cosc050sp17/home

0 Found: http://old-www.cs.dartmouth.edu/~cs50/Schedule.pdf

0 IgnExtrn: http://old-www.cs.dartmouth.edu/~cs50/Schedule.pdf

0 Found: http://www.cs.dartmouth.edu/~cs50/Logistics/

0 IgnExtrn: http://www.cs.dartmouth.edu/~cs50/Logistics/

0 Found: http://www.cs.dartmouth.edu/~cs50/Lectures/

0 IgnExtrn: http://www.cs.dartmouth.edu/~cs50/Lectures/

0 Found: http://www.cs.dartmouth.edu/~cs50/Reading/

0 IgnExtrn: http://www.cs.dartmouth.edu/~cs50/Reading/

0 Found: http://www.cs.dartmouth.edu/~cs50/examples/

0 IgnExtrn: http://www.cs.dartmouth.edu/~cs50/examples/

0 Found: http://www.cs.dartmouth.edu/~cs50/Sections/

0 IgnExtrn: http://www.cs.dartmouth.edu/~cs50/Sections/

0 Found: http://www.cs.dartmouth.edu/~cs50/Labs/

0 IgnExtrn: http://www.cs.dartmouth.edu/~cs50/Labs/

0 Found: http://www.cs.dartmouth.edu/~cs50/Labs/Project/

0 IgnExtrn: http://www.cs.dartmouth.edu/~cs50/Labs/Project/

0 Found: https://gitlab.cs.dartmouth.edu

0 IgnExtrn: https://gitlab.cs.dartmouth.edu

0 Found: http://www.cs.dartmouth.edu/~cs50/Resources/

0 IgnExtrn: http://www.cs.dartmouth.edu/~cs50/Resources/

0 Found: http://old-www.cs.dartmouth.edu/~dfk/

0 Added: http://old-www.cs.dartmouth.edu/~dfk/

1 Fetched: http://old-www.cs.dartmouth.edu/~dfk/

1 Saved: http://old-www.cs.dartmouth.edu/~dfk/

1 Fetched: http://old-www.cs.dartmouth.edu/~cs50/

1 Saved: http://old-www.cs.dartmouth.edu/~cs50/

Notice how I printed the depth of the current crawl at left, then indented slightly based on the current depth, then printed a single word meant to indicate what is being done, then printed the URL.

By ensuring a consistent format, and choosing a simple/unique word for each type of line, I can post-process the output with grep, awk, and so forth, enabling me to run various checks on the output of the crawler.

Much better than a mish-mash of arbitrary output formats!

To make this easy, I wrote a simple function to print those lines:

// log one word (1-9 chars) about a given url

inline static void logr(const char *word, const int depth, const char *url)

{

printf("%2d %*s%9s: %s\n", depth, depth, "", word, url);

}

I thus have just one printf call, and if I want to tweak the format, I just need to edit one place and not every log-type printf in the code.

Notice the

inlinemodifier. This means that C is allowed to compile this code ‘in line’ where the function call occurs, rather than compiling code that actually jumps to a function and returns. Syntactically, in every way, it’s just like a function - but more efficient. Great for tiny functions like this one, where it’s worth duplicating the code (making the executable bigger) to save time (making the program run slightly faster).

Anyway, at strategic points in the code, I make a call like this one:

logr("Fetched", page->depth, page->url);

Contents of pageDirectory after crawler has run

For each URL crawled the program creates a file and places in the file the URL and filename followed by all the contents of the webpage. But for a maxDepth = 1 as in this example there are only a few webpages crawled and files created. Below is a peek at the files created during the above crawl. Notice how each page starts with the URL, then a number (the depth of that page during the crawl), then the contents of the page (here I printed only the first line of the content).

$ ls

1 2 3

$ head -3 1

http://old-www.cs.dartmouth.edu/~cs50/index.html

0

<!DOCTYPE html>

$ head -3 2

http://old-www.cs.dartmouth.edu/~dfk/

1

<!DOCTYPE HTML PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD HTML 4.01 Transitional//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/html4/loose.dtd">

$ head -3 3

http://old-www.cs.dartmouth.edu/~cs50/

1

<!DOCTYPE html>

Organization of the TSE code

Let’s take a look at the structure of the TSE solution - so you can see what you’re aiming for.

Directory structure

My TSE comprises six subdirectories:

- libcs50 - a library of code we provide

- common - a library of code you write

- crawler - the crawler

- indexer - the indexer

- querier - the querier

- data - with subdirectories where the crawler and indexer can write files, and the querier can read files.

My top-level .gitignore file excludes data from the repository, because the data files are big, changing often, and don’t deserve to be saved.

The full tree looks like this:

├── common

│ ├── index.c

│ ├── index.h

│ ├── Makefile

│ ├── pagedir.c

│ ├── pagedir.h

│ ├── word.c

│ └── word.h

├── crawler

│ ├── crawler.c

│ ├── crawlertest.sh

│ ├── Makefile

│ └── README.md

├── indexer

│ ├── indexer.c

│ ├── indexsort.awk

│ ├── indexsort.sh

│ ├── indextest.c

│ ├── indextest.sh

│ ├── Makefile

│ └── README.md

├── libcs50

│ ├── bag.c

│ ├── bag.h

│ ├── counters.c

│ ├── counters.h

│ ├── file.c

│ ├── file.h

│ ├── file.md

│ ├── hashtable.c

│ ├── hashtable.h

│ ├── jhash.c

│ ├── jhash.h

│ ├── Makefile

│ ├── memory.c

│ ├── memory.h

│ ├── memory.md

│ ├── README.md

│ ├── set.c

│ ├── set.h

│ ├── webpage.c

│ ├── webpage_fetch.c

│ ├── webpage.h

│ ├── webpage_internal.h

│ └── webpage.md

├── Makefile

├── querier

│ ├── fuzzquery.c

│ ├── Makefile

│ ├── querier.c

│ ├── README.md

│ └── testqueries

└── README.md

Source files

My crawler, indexer, and querier each consist of just one .c file.

They share some common code, which I keep in the common directory:

- pagedir - a suite of functions to help the crawler write pages to the pageDirectory and help the indexer read them back in

- index - a suite of functions that implement the “index” data structure; this module includes functions to write an index to a file (used by indexer) and read an index from a file (used by querier).

- word - a function

NormalizeWordused by both the indexer and the querier.

Each of the program directories (crawler, indexer, querier) include a few files related to testing, as well.

You’ll recognize the Lab3 data structures - they’re all in the libcs50 library.

Note the flatter organization - there’s not a separate subdirectory (with Makefile or test code) for each data structure.

Makefiles

The starter kit includes a Makefile at the top level and another to build the libcs50 library.

The top-level Makefile recursively calls Make on each of the source directories.

The libcs50/Makefile demonstrates how you can build a library, in this case libcs50.a, from a collection of object .o files.

Study this Makefile, because you’ll need to write something similar for your common directory.

You can then link these libraries into your other programs without having to list all the individual .o files on the commandline.

For example, when I build my crawler Make runs commands as follows:

make -C crawler

gcc -Wall -pedantic -std=c11 -ggdb -DAPPTEST -I../libcs50 -I../common -c -o crawler.o crawler.c

gcc -Wall -pedantic -std=c11 -ggdb -DAPPTEST -I../libcs50 -I../common crawler.o ../common/common.a ../libcs50/libcs50.a -lcurl -o crawler

The crawler/Makefile is written in good style, with appropriate use of variables, so the rule that causes Make to run the above commands is actually much shorter:

crawler: crawler.o $(LLIBS)

$(CC) $(CFLAGS) $^ $(LIBS) -o $@

We’ll work more with Makefiles in upcoming classes.

Activity

In today’s activity your group will run the crawler over a set of web pages and try to understand why it takes the steps it does.