Software design methodology

Goals

In this lecture, we introduce a simple software design methodology. It’s by no means the only methodology - but it’s straightforward and useful for CS50.

All programmers are optimists – Frederick P. Brooks, Jr.

Here’s a cool source of thoughtful maxims for software development: The Pragmatic Programmer, by Andrew Hunt and David Thomas (2000, Addison Wesley). Their book is super, and their “tip list” is available on the web. We sprinkle some of their tips throughout the lectures.

Software system design methodology

There are many techniques for the design and development of good code including top-down or bottom-up design; divide and conquer (breaking the system down into smaller more understandable components), structured design (data flow-oriented design approach), and object-oriented design (modularity, abstraction, and information-hiding). For a quick survey of these and other techniques, see A Survey of Major Software Design Methodologies (author unknown).

Many of these techniques use similar approaches, and embrace fundamental concepts like abstraction, data representation, data flow, data structures, and top-down decomposition from requirements to structure.

It seems unlikely that someone could give you 10 steps to follow and be assured of great system software. Every non-trivial project has its special cases, unique environments, or unexpected uses. It’s often best to begin development of a module, or a system, with small experiments - building a prototype and throwing it away - because you can learn (and make mistakes) building small prototype systems.

Prototype to Learn. Prototyping is a learning experience. Its value lies not in the code you produce, but in the lessons you learn.

Clarity comes from the experience of working from requirements, through system design, implementation and testing, to integration and customer feedback on the requirements.

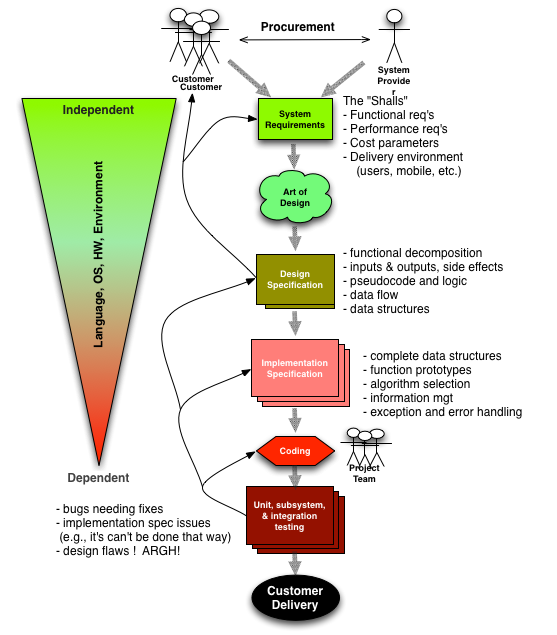

The following figure shows the software design methodology that we use in the design of the TinySearchEngine and the project.

Let’s step through the phases of software design, as shown in the figure above.

Procurement phase

The procurement phase of a project represents its early stages. It represents deep discussion between a customer and provider of software systems. As a software developer, you have to clearly understand and capture the customers’ needs. In our case, you are the provider and we (CS50 staff) are your customer.

Requirements Spec

Don’t Gather Requirements – Dig for Them. Requirements rarely lie on the surface. They’re buried deep beneath layers of assumptions, misconceptions, and politics.

The system Requirements Spec captures all the requirements of the system that the customer wants built. Typically the provider and customer get into deep discussion of requirements and their cost. The requirements must be written down, and reviewed by both customer and provider, to be sure all are in agreement. Sometimes these documents are written in contractual (legal) language. If the customer gets a system that does not meet the spec, or the two parties disagree about whether the finished product meets the spec, lawyers may get involved. If a system is late, financial penalties may arise.

“The hardest part of design… is keeping features out.” – Anonymous

The system requirement spec may have a variety of requirements typically considered the SHALLS - such as, “the crawler SHALL crawl 1000 sites in 5 minutes”. These requirements include functional requirements, performance requirements, security requirements, and cost requirements.

A common challenge during this phase is that the customer either doesn’t know what he/she really wants or expresses it poorly (in some extreme cases the customer may not be able to provide you with the ultimate intended use of your system due to proprietary or security concerns). You must realize that the customer may have these difficulties and iterate with the customer until you both are in full agreement. One useful technique is to provide the customer with the system requirements specification (and sometimes later specs too) and then have the customer explain the spec to us. It is amazing how many misunderstandings and false assumptions come to light when the customer is doing the explaining.

The Requirements Spec may address many or all of the following issues:

- functionality - what should the system do?

- performance - goals for speed, size, energy efficiency, etc.

- cost - goals for cost, if system operation incurs costs

- compliance - with federal/state law or institutional policy

- compatibility - with standards or with existing systems

- security - against a specific threat model under certain trust assumptions

A new concern of system development is the issue of the services-oriented model referred to as the “cloud” (Software As A Service, Infrastructure As A Service, etc.). The decision of whether to develop a specific system running in a traditional manner or to build a cloud-based solution should be made early, as it will affect many of the later stages of the development process. Some would argue about where it needs to fit in the methodology, but we feel that the sooner you (and the customer) know where this system is headed, the better.

Make quality a requirements issue. Involve your users in determining the project’s real quality requirements.

Although the customer may make some assumptions on this point, it’s in your best interests to make it a priority. Remember the “broken window theory”.

Don’t Live with Broken Windows. Fix bad designs, wrong decisions, and poor code when you see them.

Design Spec

The Design Spec is the result of studying the system requirements and applying the art of design (the magic) with a design team. In this phase, you translate the requirements into a full system-design specification. This design specification shows how the complete system is broken up into specific subsystems, and all of the requirements are mapped to those subsystems. The Design spec for a system, subsystem, or module includes:

- User interface

- Inputs and outputs

- Functional decomposition into modules

- Dataflow through modules

- Pseudo code (plain English-like language) for logic/algorithmic flow

- Major data structures

- Testing plan

To this last point:

Design to Test. Start thinking about testing before you write a line of code.

The Design Specification is independent of your choice of language, operating system, and hardware. In principle, it could be implemented in any language from Java to micro-code and run on anything from a Cray supercomputer to a toaster.

Implementation phase

In this phase, we turn the Design Spec into an Implementation Spec, then code up the modules, unit-test each module, integrate the modules and test them as an integrated sub-system and then system.

Implementation Spec

The Implementation Spec represents a further refinement and decomposition of the system. It is language, operating system, and hardware dependent (in many cases, the language abstracts the OS and HW out of the equation but not in this course). The implementation spec includes many or all of these topics:

- Detailed pseudo code for each of the objects/components/functions,

- Definition of detailed APIs, interfaces, function prototypes and their parameters,

- Data structures (e.g.,

structnames and members), - Security and privacy properties,

- Error handling and recovery,

- Resource management,

- Persistant storage (files, database, etc).

Coding

Coding is often the fun part of the software development cycle - but not usually the largest amount of time. As a software developer in industry, you might spend only about 20% of your time coding (perhaps a lot more if you’re in a startup). The rest of the time will be dealing with the other phases of the methodology, particularly, the last few: testing, integration, fixing problems with the product and meetings with your team and with your customers.

Goals during coding:

-

Correctness: The program is correct (i.e., does it work) and error free. Duh.

-

Clarity: The code is easy to read, well commented, and uses good variable and function names. In essence, is it easy to use, understand, and maintain

Clarity makes sure that the code is easy to understand by people with a range of skills, and across a variety of machine architectures and operating systems. [Kernighan & Pike]

-

Simplicity: The code is as simple as possible, but no simpler.

Simplicity keeps the program short and manageable. [Kernighan & Pike]

-

Generality: The program can easily adapt to change.

Generality means the code can work well in a broad range of situations and is tolerant of new environments (or can be easily made to do so). [Kernighan & Pike]

Unit and sub-system testing

Test your software, or your users will.

Testing is a critical part of the whole process of any development effort, whether you’re building bridges or software. Unit testing of modules in isolation, and integration testing as modules are assembled into sub-systems and, ultimately, the whole system, result in better, safer, more reliable code. We’ll talk more about testing soon.

The ultimate goal of testing is to exercise all paths through the code. Of course, with most applications this may prove to be a daunting task. Most of the time the code will execute a small set of the branches in the module. So when special conditions occur and newly executed code paths fail, it can be really hard to find those problems in large complex pieces of code.

The better organized and modularized your code is, the easier it will be to understand, test, and maintain - even by you!

Write test scripts (tools) throughout the development process to quickly give confidence that even though 5% of new code has been added, no new bugs emerged because our test scripts assured of that.

Integration testing

The system is incrementally developed, put together and tested at various levels. Subsystems could integrate many modules, and sometimes, new hardware. The developer will run the integrated system against the original requirements to see if there are any ‘gotchas’. For example, some performance requirements can only be tested once the full system comes together, while other, commonly used utility functions could have performance analysis done on them early on. You can simulate external influences as well, such as increasing the external processing or communications load on the host system as a way to see how your program operates when the host system is heavily loaded or resource limited.

To quote the Pragmatic Programmer again:

Pragmatic Programmer Tip : Don’t Think Outside the Box – Find the Box.

When faced with an impossible problem, identify the real constraints. Ask yourself: “Does it have to be done this way? Does it have to be done at all?”

Feedback phase

In this phase, the design team sits down with its customer and demonstrates its implementation. The customer and the team review the original requirement spec and check each requirement for completion.

In the TSE and project we emphasize understanding the requirements of the system we want to build, writing good design and implementation specs before coding. You shall apply the coding principles of simplicity, clarity, and generality (we will put more weight on these as we move forward with assignments and the project).